A less loud city

Born in St.Petersburg, they live in Tallinn. It seems to be the only thing uniting Russian migrants of different waves in Estonia

Modular multi-story houses, standard boxes of kindergartens, empty lots with a grid of improvised paths. Beaten right through the grass lawn, those paths will safely take you to the closest grocery store unlike the pavement road. This is how people make the area habitable, the "urban nightmare" of Soviet quarters invented in paper plans not for the comfort of living, but for fast completion of the development plan.

Lasnamae waltz

Lasnamäe in Tallinn. The largest area in the Estonian capital with the biggest concentration of Russians was ill-famed as a proletarian district twenty years ago.

Today Estonians also come to live here and assimilate, but one hears predominantly Russian speech. Grey boxes of modular houses are undergoing renovation" showing up patches of all the colors of the rainbow – from sky blue to orange. Supermarkets lure in customers from the nearby areas with low prices. However, the past is showing up like a fresco painting through the plaster.

Lasnamäe was erected in 1960-s by construction workers from the whole Soviet Union. Behind the houses there is an industrial area separated from the city by Petersburg highway. They also have Moscow boulevard (Moskva puiestee) and Square of Patriarch Alexy II (Patriarh Aleksius II väljak), who was born in Tallinn.

In Mustakivi Keskus mall, about ten stores are filled with European consumer goods and Turkish stuff. A smell of cabbage pies comes from a Soviet-looking café. Few people want to get nostalgic, just a stout blond woman is chewing a pie by the window.

In Mustakivi Keskus mall, about ten stores are filled with European consumer goods and Turkish stuff. A smell of cabbage pies comes from a Soviet-looking café. Few people want to get nostalgic, just a stout blond woman is chewing a pie by the window.

Lasnamäe district, Tallinn

Drop-off location

Next to an unremarkable store with stuff for women, there is a drop-off location for announcements to be published in the last advertising newspaper in entire Estonia. From the pages of this newspaper one can learn that "a retired man, who is a good household keeper, is looking for a woman, who will not be scared away by hens, a greenhouse and a good garden", and "a 64 year old professional in the prime of life will do work with his own tools on detecting defects in the water supply piping". In the next column they sell piano "Riga", buy copper cable, look for students to attend training courses for welders and Bible studies, invite to find a job abroad, offer services on evacuation of abandoned cars and purchase spare parts for Soviet motorbikes. If someone decides to create an encyclopedia of Russian life in Estonia, it is hard to find a better source than a newspaper with announcements.

Next to an unremarkable store with stuff for women, there is a drop-off location for announcements to be published in the last advertising newspaper in entire Estonia. From the pages of this newspaper one can learn that "a retired man, who is a good household keeper, is looking for a woman, who will not be scared away by hens, a greenhouse and a good garden", and "a 64 year old professional in the prime of life will do work with his own tools on detecting defects in the water supply piping". In the next column they sell piano "Riga", buy copper cable, look for students to attend training courses for welders and Bible studies, invite to find a job abroad, offer services on evacuation of abandoned cars and purchase spare parts for Soviet motorbikes. If someone decides to create an encyclopedia of Russian life in Estonia, it is hard to find a better source than a newspaper with announcements.

Lasnamäe district, Tallinn

the first wave story

Zhanna

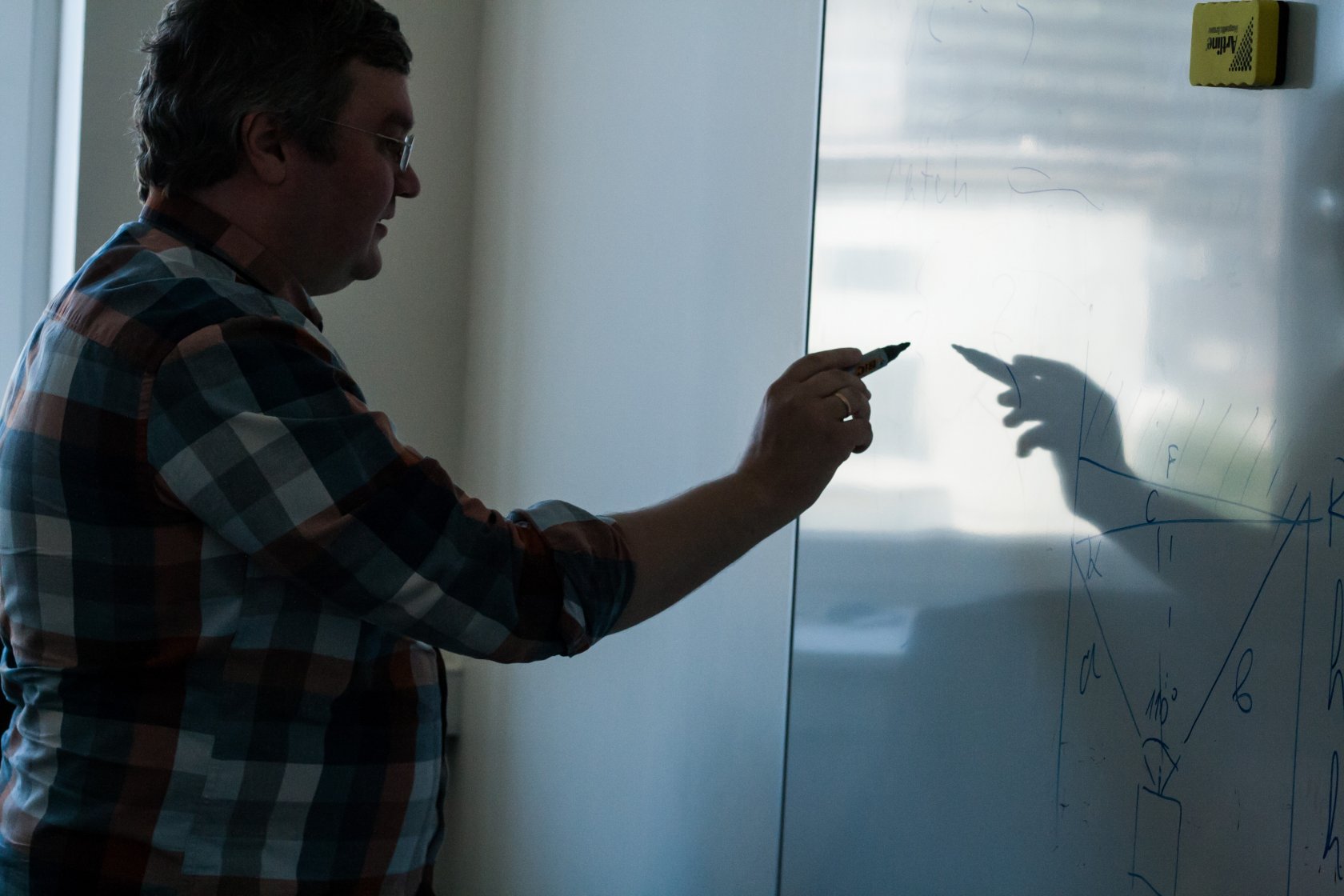

Zhanna Einmann is an advertising manager in the newspaper. The room is full of sunlight – it comes through the blinds drawing stripes on the office table. Zhanna is making an espresso for me. She is a little over forty.

Zhanna moved to Estonia 24 years ago. She left St.Petersburg following her Estonian husband, whom she met at the institute during his studies. After graduation they almost stayed in St.Petersburg, but the housing situation was tough there. So they recklessly exchanged two rooms in St.Petersburg for a whole apartment in Narva.

"At that time I thought: just a two hour drive and I'm in Petersburg", explains Zhanna. She went to St.Petersburg almost every month to visit her parents.

Then the borders appeared. The family moved to Narva right before Gorbachev granted freedom to the Baltic republics (The USSR president Mikhail Gorbachev confirmed the Constitutional right of the Estonian Republic to exit the Soviet Union on January 28, 1991). Their son was born already in Narva. The year of 1991 Zhanna spent in between the two cities continuing to work in St.Petersburg, although her husband already moved to Estonia.

In Narva Zhanna worked as a store manager selling goods for sewing. Then, she started to work with advertising in a Narva newspaper and later on television. After moving to Tallinn she found a job with a newspaper, where she has stayed during the recent years.

Then the borders appeared. The family moved to Narva right before Gorbachev granted freedom to the Baltic republics (The USSR president Mikhail Gorbachev confirmed the Constitutional right of the Estonian Republic to exit the Soviet Union on January 28, 1991). Their son was born already in Narva. The year of 1991 Zhanna spent in between the two cities continuing to work in St.Petersburg, although her husband already moved to Estonia.

In Narva Zhanna worked as a store manager selling goods for sewing. Then, she started to work with advertising in a Narva newspaper and later on television. After moving to Tallinn she found a job with a newspaper, where she has stayed during the recent years.

Zhanna at work

Two languages

Any conversation in Tallinn sooner or later comes down to the discussion whether you have to study Estonian or not. A lot is related to the Estonian language in Zhanna's life: from the new job prospects to communication with her husband's friends and relatives. The job market is unofficially divided based on the knowledge of the language.

Zhanna admits that she is not worried about the problem of "non-citizens" in Estonia, however a lot of her Russian acquaintances are not ready to take the Estonian language exam as a matter of principle. Moreover, in order to become a citizen, "non-citizens" should prove not only the command of language, but also familiarity with the Constitution and citizenship law.

Any conversation in Tallinn sooner or later comes down to the discussion whether you have to study Estonian or not. A lot is related to the Estonian language in Zhanna's life: from the new job prospects to communication with her husband's friends and relatives. The job market is unofficially divided based on the knowledge of the language.

Zhanna admits that she is not worried about the problem of "non-citizens" in Estonia, however a lot of her Russian acquaintances are not ready to take the Estonian language exam as a matter of principle. Moreover, in order to become a citizen, "non-citizens" should prove not only the command of language, but also familiarity with the Constitution and citizenship law.

«Non-citizens»

According to the law "On foreigners" of 1993, the "non-citizen" status was granted to approximately 12% of predominantly Russian population living in the Republic before the collapse of the Soviet Union and failing to get the citizenship after. "Non-citizens" are not allowed to become party members or create parties, and take part in the European Parliament elections. They can vote at the local elections, though. This status imposes limitations on the professional choice and real estate acquisition. By 2016 the number of "non-citizens" came down from 12% to 6% of the country population, but there are still over 81 thousand of them. In September of 2015 the European Parliament adopted a resolution that announced the "non-citizens" living in the EU and particularly in Estonia to be the victims of discrimination.

"The I-was-born-here-why-should-I-take-any-exams viewpoint is very common among Russians in Estonia," says Zhanna. "The Russians were invited here to work and raise the economy. For example, in Finland and Sweden they have two languages, but the policy in Estonia is different - it's our country and we want you to speak Estonian. But it's not the people's fault that they found themselves here. If they cannot or don't want to learn the language, it's their right."

However, personally Zhanna decided otherwise and took the exam. She became an Estonian citizen in 2007, but in the course of 24 years she still has not fully transitioned to the Estonian language. She speaks Russian at work and with her Estonian husband, speaking Estonian only with his friends. "I keep silent for the most part, but at least I generally understand what they are talking about." They stopped being friends with one Estonian family after they announced they were not going to communicate with Zhanna because she didn't speak Estonian. "My husband is trying to speak in Estonian to me more and more, but it's hard for me. I start making mistakes and he corrects me," adds Zhanna. The desire to communicate wins over the language battles and the spouses turn to Russian every time.

In August Zhanna promised herself to take the Estonian language course for B1 level exam (the level that allows to understand the general idea of the conversation). The government pays for the courses, but it's hard to enter them. Zhanna prepared for it using an Internet language training simulator.

Showing who is right

Consent on the language issue comes in front of the TV. Together with her husband Zhanna watches both Russian and Estonian channels.

On the "menu" they have "NTV-Mir", the First channel and "The First Baltic", a TV company created by the First channel to broadcast in the Baltic countries. Zhanna watches only the news in Estonian channels. She is accustomed to Russian TV and considers local TV to be small-scale ("What can possibly happen here?"). She is skeptical about the Internet saying "I don't like to spend a lot of time there, I get enough of it at work."

When talking about Russian television, Zhanna changes dramatically and one can hear notes of steal breaking through the soft voice.

"It's important to show the truth," she says. "Why others are talking about the truth at every corner, while we are not able to protect ourselves? Of course, Lavrov (the RF Minister of Foreign Affairs. – author's note) speaks up, but all of it goes down the drain, it stays unnoticed. Here only the European Union viewpoint is shown. You only hear that we are the invaders, the invaders."

"I'm for the Crimea, of course. Russian TV showed a film saying that 90% of the Crimea citizens wanted to separate. Not even a word was mentioned about it here. Only "invasion" and "force". Personally, it offends me".

When Zhanna tried to retell to her Estonian friends the film content saying that the Ukranian government did nothing but destruction during the last 20 years, they refused to listen to her. "They don't even want to understand it," she concludes. "We try not to touch upon these topics. I know everything they are going to say and they know how I can reply."

To my question whether Zhanna considers herself a Russian or an Estonian, she cuts it short "I've always been Russian and I'll stay this way forever. I defend Russia, sometimes even shouting out loud, strenuously. I will always take the Russian side, even though my husband is Estonian. I attend local festivities with no resistance. However, if I lived in a Russian family, I wouldn't do it. Russian celebrations are joyful and here they are boring".

"Historically they lived in isolated farmsteads, which brought about lack of hospitality and uncordial attitude to others," explains Zhanna. "A Russian person will meet everyone with hospitality, while they don't like a lot of guests. In Russia when we had 5 or 6 relatives visiting us in a two room apartment, nobody complained. The Estonians get tired of it. However, they like to work hard, in this sense they are doing a good job."

All that said, a logical question comes up: What keeps you in Estonia? Zhanna immediately replies that it is her family. If it weren't for the husband, she would have come back to St.Petersburg long time ago. Her mother, her sister and nephews live there. "I have everyone there," sighs Zhanna, "and nobody but my husband and my son here."

"To tell you the truth," suddenly concludes Zhanna, "if I had known about the borders, the separation of people and no opportunity to visit home, may be I would not have moved to Estonia at all".

Kadriorg and Petersburg

Zhanna often comes back to visit St.Petersburg that she calls home. "Tallinn is a very quiet city. I've got accustomed to it and calmed down myself. There's nowhere to rush. It's like a little swamp, frankly speaking. When in St.Petersburg, I go running, they won't let you stay for too long. When I come back from there, I have a different kind of energy and everybody notices it. Then, it shrinks, goes down, lower and lower and you are like everyone again…"

However, personally Zhanna decided otherwise and took the exam. She became an Estonian citizen in 2007, but in the course of 24 years she still has not fully transitioned to the Estonian language. She speaks Russian at work and with her Estonian husband, speaking Estonian only with his friends. "I keep silent for the most part, but at least I generally understand what they are talking about." They stopped being friends with one Estonian family after they announced they were not going to communicate with Zhanna because she didn't speak Estonian. "My husband is trying to speak in Estonian to me more and more, but it's hard for me. I start making mistakes and he corrects me," adds Zhanna. The desire to communicate wins over the language battles and the spouses turn to Russian every time.

In August Zhanna promised herself to take the Estonian language course for B1 level exam (the level that allows to understand the general idea of the conversation). The government pays for the courses, but it's hard to enter them. Zhanna prepared for it using an Internet language training simulator.

Showing who is right

Consent on the language issue comes in front of the TV. Together with her husband Zhanna watches both Russian and Estonian channels.

On the "menu" they have "NTV-Mir", the First channel and "The First Baltic", a TV company created by the First channel to broadcast in the Baltic countries. Zhanna watches only the news in Estonian channels. She is accustomed to Russian TV and considers local TV to be small-scale ("What can possibly happen here?"). She is skeptical about the Internet saying "I don't like to spend a lot of time there, I get enough of it at work."

When talking about Russian television, Zhanna changes dramatically and one can hear notes of steal breaking through the soft voice.

"It's important to show the truth," she says. "Why others are talking about the truth at every corner, while we are not able to protect ourselves? Of course, Lavrov (the RF Minister of Foreign Affairs. – author's note) speaks up, but all of it goes down the drain, it stays unnoticed. Here only the European Union viewpoint is shown. You only hear that we are the invaders, the invaders."

"I'm for the Crimea, of course. Russian TV showed a film saying that 90% of the Crimea citizens wanted to separate. Not even a word was mentioned about it here. Only "invasion" and "force". Personally, it offends me".

When Zhanna tried to retell to her Estonian friends the film content saying that the Ukranian government did nothing but destruction during the last 20 years, they refused to listen to her. "They don't even want to understand it," she concludes. "We try not to touch upon these topics. I know everything they are going to say and they know how I can reply."

To my question whether Zhanna considers herself a Russian or an Estonian, she cuts it short "I've always been Russian and I'll stay this way forever. I defend Russia, sometimes even shouting out loud, strenuously. I will always take the Russian side, even though my husband is Estonian. I attend local festivities with no resistance. However, if I lived in a Russian family, I wouldn't do it. Russian celebrations are joyful and here they are boring".

"Historically they lived in isolated farmsteads, which brought about lack of hospitality and uncordial attitude to others," explains Zhanna. "A Russian person will meet everyone with hospitality, while they don't like a lot of guests. In Russia when we had 5 or 6 relatives visiting us in a two room apartment, nobody complained. The Estonians get tired of it. However, they like to work hard, in this sense they are doing a good job."

All that said, a logical question comes up: What keeps you in Estonia? Zhanna immediately replies that it is her family. If it weren't for the husband, she would have come back to St.Petersburg long time ago. Her mother, her sister and nephews live there. "I have everyone there," sighs Zhanna, "and nobody but my husband and my son here."

"To tell you the truth," suddenly concludes Zhanna, "if I had known about the borders, the separation of people and no opportunity to visit home, may be I would not have moved to Estonia at all".

Kadriorg and Petersburg

Zhanna often comes back to visit St.Petersburg that she calls home. "Tallinn is a very quiet city. I've got accustomed to it and calmed down myself. There's nowhere to rush. It's like a little swamp, frankly speaking. When in St.Petersburg, I go running, they won't let you stay for too long. When I come back from there, I have a different kind of energy and everybody notices it. Then, it shrinks, goes down, lower and lower and you are like everyone again…"

Kadriorg is Zhanna's favourite place to walk around. The park was named Katharinas Tal after Katherine, the spouse of Peter I. The residence of the Russian emperor was located here. "It's the only place of the kind in Tallinn and it reminds me of our Russian architecture in miniature."

In the end of our conversation I ask Zhanna if she is thinking of coming back to Russia. She replies: "I don't even know what's the procedure. They will probably give the Russian citizenship back, but it can be difficult. May be not in my case. I was born there, I'm a former USSR citizen. I don't think it's such a big problem. They will accept those who really want to come back…"

The question remains open-ended. It turns out that to have an appointment in the Russian Consulate in Tallinn, people get in line the day before. "They are open only for 2 or 3 hours not even every day. Go and try to get there!" concludes Zhanna.

The question remains open-ended. It turns out that to have an appointment in the Russian Consulate in Tallinn, people get in line the day before. "They are open only for 2 or 3 hours not even every day. Go and try to get there!" concludes Zhanna.

The second wave story

Aleksey

We meet with Aleksey M. , a 44 years old man who has lived in Estonia for seven years, in Lido café downtown Tallinn. He often comes here for lunch because of the large portions and good food at reasonable prices.

"I grew up next door from the Hermitage. Piotrovsky's place was at one staircase with ours," Alexey recalls the details of his life in St.Petersburg. "It was the house of the Hermitage workers. One of my ancestors was related to the museum."

Alexey's parents have education in technical sciences. "I saw a computer at my mom's work at the age of seven for the first time," he tells his story. "These were large boxes that took two or three rooms."

Alexey's parents have education in technical sciences. "I saw a computer at my mom's work at the age of seven for the first time," he tells his story. "These were large boxes that took two or three rooms."

Since that meeting with those giant machines, Alexy had no doubts as to his future occupation entering the IT professional sphere.

At first, he worked with electronics and electric engineering, but he found himself in system administration. He received no "wallpaper degree" from the university, although he studied at several institutions in St.Petersburg including the Bonch-Bruevich Institute of telecommunications.

At first, he worked with electronics and electric engineering, but he found himself in system administration. He received no "wallpaper degree" from the university, although he studied at several institutions in St.Petersburg including the Bonch-Bruevich Institute of telecommunications.

A quieter city

Alexey admits that he has never though he would become a migrant one day. "I had no thoughts about moving abroad at all. However, I was thinking about moving from St.Petersburg to a quieter town. I don't like living in such a busy place."

"It's certainly great to come to Nevsky Prospect in the evening," recalls he. "You can walk around Palace Square, of course, but then you have to spend hours in the traffic jams to get back home…"

The housing problem comes up as well. There were no chances to buy their own housing for the family, although Alexey had a good income. By the time he decided to leave, the employees in his company received their salary in foreign currency.

"It's the time of economic crisis", he is telling, "and on the salary day all the nearby exchange offices run out of rubles. My colleagues just took out all the cash."

Their own housing was out of the question, it required a different income level. Together with his wife and two daughters Alexey though about moving to Petrozavodsk, but they ended up in Tallinn.

It was a matter of chance.

On the border

Like many citizens of St.Petersburg, Alexey often traveled to Finland. It was almost a regular weekend trip. As for Estonia, it took a while before he focused on this country. For a long time Estonia was not a part of Schengen zone and obtaining a visa was a little harder.

It happened to be quite easy to move. Alexey registered a tiny company (by the way there's no income tax in Estonia) and received residence permit for two years. The family managed to move in one year. That's how a Russian IT specialist became an Estonian entrepreneur. And he was not the only one of the kind. Other Russians found occupation in the sphere of services for the most part: they opened cafés, recreation areas, and small IT companies as well.

On the moving day Alexey loaded his station car and drove to the Russian-Estonian border. He managed to move all belongings in two trips feeling nervous that the border officers would pick at him for some reason. "They just laughed at me at the customs: the car was stuck with stuff that there was no place for a second person," he tells. "At the Russian border the officer said "Open your car. Take everything out". But once I barely managed to unload one huge box, they immediately said "Ok, don't take it out, just leave."

That's how Alexey left Russia. The boarder officers jokingly promised to collect customs duty for the old microwave.

Between the two shores

Moving was much easier than socializing in a new place. "We are still on our own," continues Alexey. "Although the local community considers themselves Russian, in fact they are even further away from us than the Estonians."

One can feel it well when watching advertising in Russian channels. "You look at them, hear their arguments and you feel as if it's 1995 in Russia," he makes an analogy, "and there's a man in a purple jacket with a BMW. It's shot with an amateur camera in a studio with the relevant messages. It reminds of the Russian society 20 years ago."

"Upon arrival my wife and I visited the Russian community gathering one evening, but we didn't feel we belonged," says Alexey, "mostly because the local Russians are truly puzzled why my wife and I decided to move to Tallinn."

"A lot of Russians here ardently support Putin, especially those who have never been to Russia. I had to explain myself to the locals many times "What? You have come from St.Petersburg? To this hole?! But why, it's so good out there, you have Putin, you have…" I'm asking them "When did you go to Russia last?" They say "Well, after the tenth grade we came to visit, but we watch the First channel!.."

"The companies are divided into Russian and Estonian," he says, "although now there are more places with English as the working language. Otherwise, if it is a team of Russian IT engineers, there are no Estonians there. And visa versa. It's not that they would turn you down because of your nationality, but you won't do it yourself and they just won't invite you for the job interview."

Alexey doesn't like it, he is into international companies. Apart from Swedes and Finns, he has worked with the French, Portuguese, Spanish and Americans. It also becomes easier to work with Russians, who have recently moved to Estonia. This wave is quite visible according to him. If at the time of exchange rate of 40-50 ruble for one euro St.Petersburg and Tallinn were at the same level in terms of salaries and prices, now Russia is losing the game.

Describing the situation Alexey talks not only about his family, but also about those who moved to Estonia for business reasons right after "the fat years of Russia". "Our community has remained on its own so far."

Alexey admits that he has never though he would become a migrant one day. "I had no thoughts about moving abroad at all. However, I was thinking about moving from St.Petersburg to a quieter town. I don't like living in such a busy place."

"It's certainly great to come to Nevsky Prospect in the evening," recalls he. "You can walk around Palace Square, of course, but then you have to spend hours in the traffic jams to get back home…"

The housing problem comes up as well. There were no chances to buy their own housing for the family, although Alexey had a good income. By the time he decided to leave, the employees in his company received their salary in foreign currency.

"It's the time of economic crisis", he is telling, "and on the salary day all the nearby exchange offices run out of rubles. My colleagues just took out all the cash."

Their own housing was out of the question, it required a different income level. Together with his wife and two daughters Alexey though about moving to Petrozavodsk, but they ended up in Tallinn.

It was a matter of chance.

On the border

Like many citizens of St.Petersburg, Alexey often traveled to Finland. It was almost a regular weekend trip. As for Estonia, it took a while before he focused on this country. For a long time Estonia was not a part of Schengen zone and obtaining a visa was a little harder.

It happened to be quite easy to move. Alexey registered a tiny company (by the way there's no income tax in Estonia) and received residence permit for two years. The family managed to move in one year. That's how a Russian IT specialist became an Estonian entrepreneur. And he was not the only one of the kind. Other Russians found occupation in the sphere of services for the most part: they opened cafés, recreation areas, and small IT companies as well.

On the moving day Alexey loaded his station car and drove to the Russian-Estonian border. He managed to move all belongings in two trips feeling nervous that the border officers would pick at him for some reason. "They just laughed at me at the customs: the car was stuck with stuff that there was no place for a second person," he tells. "At the Russian border the officer said "Open your car. Take everything out". But once I barely managed to unload one huge box, they immediately said "Ok, don't take it out, just leave."

That's how Alexey left Russia. The boarder officers jokingly promised to collect customs duty for the old microwave.

Between the two shores

Moving was much easier than socializing in a new place. "We are still on our own," continues Alexey. "Although the local community considers themselves Russian, in fact they are even further away from us than the Estonians."

One can feel it well when watching advertising in Russian channels. "You look at them, hear their arguments and you feel as if it's 1995 in Russia," he makes an analogy, "and there's a man in a purple jacket with a BMW. It's shot with an amateur camera in a studio with the relevant messages. It reminds of the Russian society 20 years ago."

"Upon arrival my wife and I visited the Russian community gathering one evening, but we didn't feel we belonged," says Alexey, "mostly because the local Russians are truly puzzled why my wife and I decided to move to Tallinn."

"A lot of Russians here ardently support Putin, especially those who have never been to Russia. I had to explain myself to the locals many times "What? You have come from St.Petersburg? To this hole?! But why, it's so good out there, you have Putin, you have…" I'm asking them "When did you go to Russia last?" They say "Well, after the tenth grade we came to visit, but we watch the First channel!.."

"The companies are divided into Russian and Estonian," he says, "although now there are more places with English as the working language. Otherwise, if it is a team of Russian IT engineers, there are no Estonians there. And visa versa. It's not that they would turn you down because of your nationality, but you won't do it yourself and they just won't invite you for the job interview."

Alexey doesn't like it, he is into international companies. Apart from Swedes and Finns, he has worked with the French, Portuguese, Spanish and Americans. It also becomes easier to work with Russians, who have recently moved to Estonia. This wave is quite visible according to him. If at the time of exchange rate of 40-50 ruble for one euro St.Petersburg and Tallinn were at the same level in terms of salaries and prices, now Russia is losing the game.

Describing the situation Alexey talks not only about his family, but also about those who moved to Estonia for business reasons right after "the fat years of Russia". "Our community has remained on its own so far."

Alexey's office in central Tallinn

Political factor

The decision to move was mostly taken for economic rather than political reasons. The latter was just about 10%, not more. "Yes, I'm not happy with what's going on in Russia," speculates Alexey, "on the other hand everybody confirms that there are no arrests in the open and it's not like in 1937. It's not that people are running away, but when you seriously consider moving or staying in St.Petersburg, political factor counts."

Alexey admits that his interest in the social and community life has reemerged in Estonia. "I'm following local affairs, I have a company and I'm interested in developing business here. I want market politicians to hold the office. I consider Gaidar (ideologist of market reforms in post-perestroika time in Russia. – author's note) a positive figure. Now the centrist party is trying to come to power here, their motto is "Give us social care". Those can be hard times for business. I would not want it."

He often reads forums on the Internet, but he prefers not to interact with local Russians even there. "Local forums are a nightmare! I communicate on the same platforms as before – Avito.ru and Little One."

A few years ago Alexey's elderly father was prohibited to travel abroad because of his work at a special facility. "Three years ago they took everyone's passports and have been keeping them at work," says Alexey, "and my mother is retired, it's hard for her to travel here alone."

I ask Alexey: What's next? He sighs and tells that they can apply for Estonian citizenship only in a year, but he has not decided yet if it is worth doing. It's not even about patriotism, since you can get Estonian citizenship only after refusing from the Russian one. This is the condition on the part of Estonia. Together with the application you should submit a paper confirming that you don't hold the Russian citizenship anymore. Alexey is not ready to take this step. His parents live in St.Petersburg and there have been bleak rumors within the Russian community that the Russian Consulate refuses to provide the "denied persons" with Russian visas. If you deny your citizenship, it is forever. Out of site out of mind."

The decision to move was mostly taken for economic rather than political reasons. The latter was just about 10%, not more. "Yes, I'm not happy with what's going on in Russia," speculates Alexey, "on the other hand everybody confirms that there are no arrests in the open and it's not like in 1937. It's not that people are running away, but when you seriously consider moving or staying in St.Petersburg, political factor counts."

Alexey admits that his interest in the social and community life has reemerged in Estonia. "I'm following local affairs, I have a company and I'm interested in developing business here. I want market politicians to hold the office. I consider Gaidar (ideologist of market reforms in post-perestroika time in Russia. – author's note) a positive figure. Now the centrist party is trying to come to power here, their motto is "Give us social care". Those can be hard times for business. I would not want it."

He often reads forums on the Internet, but he prefers not to interact with local Russians even there. "Local forums are a nightmare! I communicate on the same platforms as before – Avito.ru and Little One."

A few years ago Alexey's elderly father was prohibited to travel abroad because of his work at a special facility. "Three years ago they took everyone's passports and have been keeping them at work," says Alexey, "and my mother is retired, it's hard for her to travel here alone."

I ask Alexey: What's next? He sighs and tells that they can apply for Estonian citizenship only in a year, but he has not decided yet if it is worth doing. It's not even about patriotism, since you can get Estonian citizenship only after refusing from the Russian one. This is the condition on the part of Estonia. Together with the application you should submit a paper confirming that you don't hold the Russian citizenship anymore. Alexey is not ready to take this step. His parents live in St.Petersburg and there have been bleak rumors within the Russian community that the Russian Consulate refuses to provide the "denied persons" with Russian visas. If you deny your citizenship, it is forever. Out of site out of mind."

Old town. Tallinn

*****

We are standing at an observation platform over the downtown of Tallinn. A wonderful view opens from among the skyscrapers onto the City Hall Square. Alexey admits that he adores the Old Town with its windy narrow streets.

"Here I'm like everyone else. When the open market opens in the square right before Christmas, we always come here for a walk. I also like to come by the Old Town for a cup of coffee whenever I have a moment."

In the distance closer to the horizon we see the tops of four modular houses.

"Lasnamäe," nods Alexey. He used to live in the Russian district too, but now he has moved to a different area.

We are standing at an observation platform over the downtown of Tallinn. A wonderful view opens from among the skyscrapers onto the City Hall Square. Alexey admits that he adores the Old Town with its windy narrow streets.

"Here I'm like everyone else. When the open market opens in the square right before Christmas, we always come here for a walk. I also like to come by the Old Town for a cup of coffee whenever I have a moment."

In the distance closer to the horizon we see the tops of four modular houses.

"Lasnamäe," nods Alexey. He used to live in the Russian district too, but now he has moved to a different area.